How a Northern California community halted a plan to log old coast redwood trees in the Gualala River floodplain

by Jeanne Jackson

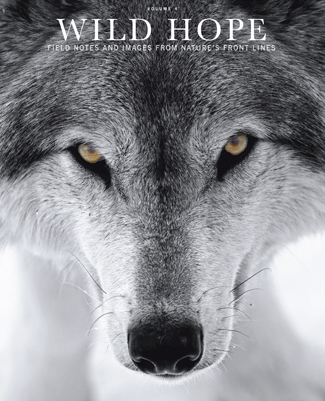

Published in Wild Hope magazine

Fall, 2017

re-printed with permission

The Gualala River empties into the Pacific Ocean at the border between Sonoma and Mendocino counties on the northern California coast. It is a wild river with no man-made impediments. Many animals call it home, including shy western pond turtles (Actinemys marmorata), endangered California red-legged frogs (Rana draytonii), and the Gualala roach (Lavinia parvipinnus), a minnow endemic to the Gualala River. Rare species of plants grow in the river’s floodplain, such as the fringed corn lily (Veratrum fimbriatum) and coast lily (Lilium maritimum).

For centuries, the Gualala River teemed with steelhead trout, and Pomo Indians, who originally settled the region, cherished the river for its water and fish, and later it became a magnet for fishermen and women from around the world. Nowadays, though, steelhead are sparse, because the river has become choked with sediment coming principally from nearby logging roads.

Much of the river’s watershed is zoned for timber harvesting, which has taken place for decades. In 2015, the Edmunds family, who had owned 30,000 acres in the Gualala River floodplain since the 1930s under the auspices of Gualala Redwoods, Inc., sold most of their holdings to Gualala Redwood Timber, Inc., owned by the Burch family. This sale was a blow to locals and the environmental and land trust groups whose bid for the land was unsuccessful.

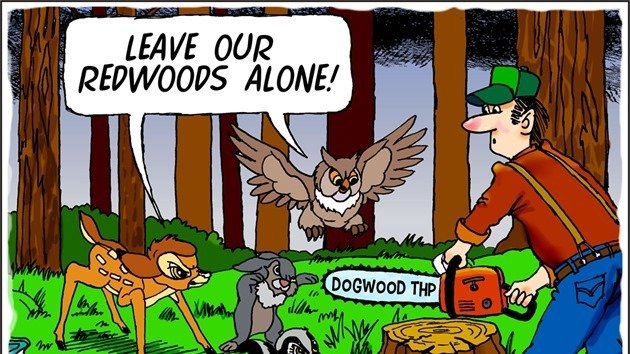

Disappointment grew when the first timber harvest plan (THP) submitted under the new ownership, dubbed “Dogwood,” would log century-old coast redwood trees in the Gualala River floodplain. The 320-acre Dogwood THP was to start at the boundary of Gualala Point Regional Campground near the mouth of the river and extend five miles upstream.

This area was logged more than a hundred years ago. It shouldn’t have been logged then, and it shouldn’t be logged now. Forest Practice Rules established by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (also known as Cal Fire), which authorizes THPs, are supposed to protect a river’s floodplain from disturbance. Putting in skid trails to remove the felled redwood trees would lead to soil erosion and cause serious damage to the floodplain, harming it for generations.

Rivers need their floodplains. When the Gualala River swells with winter rains, carrying a heavy load of soil and rocks with it, the redwood trees and other foliage catch the sediment, cleaning the river. Most trees don’t grow in floodplain, as they don’t like getting their “feet” wet, but redwood trees thrive there. We need to see these redwoods as assets to the river, playing an important part in the river’s ecosystem, rather than as board feet.

The Dogwood THP caught the attention of Dr. Peter Baye, a botanist, coastal ecologist, and board member of Friends of Gualala River (FoGR), a small but eloquent and powerful voice for protecting the river. Upon reading the THP, Baye discovered that it failed to consider the cumulative impact of logging in the Gualala River watershed and it lacked any of the surveys meant to protect sensitive habitats, such as assessments of special-status plants and wildlife. Baye and FoGR published a public warning about the destructive logging plan.

FOR GENERATIONS, locals and visitors alike have walked on the land just east of the Gualala Point Regional Campground, as a way to access the river. It’s beautiful there; locals call it the “Magical Forest.” To think of it being destroyed by logging roads and felled redwood trees is distressing to many.

I write a nature column, “Mendonoma Sightings,” in the local weekly newspaper, the Independent Coast Observer. People send me their nature sightings, often with photos, and I share them in my column. Because of this, I have come to treasure the Gualala River and its floodplain.

A statement I read by David Bolling in his book, How to Save a River, resonated with me: “Choosing to save a river is more often an act of passion than of careful calculation. You make the choice because the river has touched your life in an intimate and irreversible way, because you are unwilling to accept its loss.” With that in mind, my husband, Richard, and I decided to get involved in stopping the Dogwood THP. We, too, had walked the Magical Forest many times, often with our golden retrievers. The serenity of the flowing river, flanked by coast redwoods and lush foliage never fails to touch our hearts. It was worth saving.

There is a public comment period during which anyone can raise concerns about a particular THP. Hundreds of letters were submitted to Cal Fire. Using the website change.org, Richard and I started a petition asking Cal Fire to reject Dogwood, which several thousand people signed. Cal Fire, however, doesn’t seem to consider petitions to be legitimate public comment. Regardless, the change.org petition gave us a way to send email updates to all of those people who were as outraged by the THP as we were and also allowed us to ask for donations to FoGR when we learned Cal Fire had approved Dogwood, despite the many valid reasons for denying it.

It appeared that the only way to stop the THP was to bring legal action. Three non-profit environmental groups united to file a lawsuit against Cal Fire. FoGR was joined by Forest Unlimited, whose mission is “to protect, enhance and restore the forests and watersheds of the North Bay,” and the Dorothy King Young chapter of the California Native Plant Society, which takes an interest in public and private projects that may have an impact on native plants.

WHILE THE LAWSUIT was being drawn up, we planned a protest rally, as a way of bringing people together and giving them an opportunity to voice their concerns, and to publicize the harm the Dogwood THP would do to the river.

I contacted Sonoma County Regional Parks to find out if we could hold the rally at Gualala Point Regional Park, which overlooks the mouth of the river. I was told I needed to apply for a permit, which I did. They made it clear that County Parks wanted to support our First Amendment rights.

We settled on the date of July 16, 2016. We gathered, over two hundred strong, in the parking lot and then marched across a grassy meadow to where we had set up a portable speaker. Young and old came out in force, along with members of the Pomo tribe who consider the waters of the Gualala River sacred; they say the river is “life.” Many people brought signs bearing slogans such as “Save Our River,” “Shame on you, Cal Fire,” “Dump Dogwood,” and “Cal Fire Misfired.” It was important to our community to come together and speak for the river. If we didn’t, who else would? Time and again, we chanted, “We speak for the river!”

THE LAWSUIT WAS FILED with Sonoma County Superior Court in August 2016, where it was assigned to Judge René Chouteau. On January 25, 2017, Judge Chouteau remanded the THP back to Cal Fire, a highly unusual and heartening move, citing violations to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and the Forest Practice Rules.

So now we wait for a possible new and improved Dogwood THP. There will be another round of public comment, but the sentiments of the community will always be against logging in the floodplain of the Gualala River. Our ultimate goal is to purchase the floodplain land and add it to Gualala Point Regional Park, creating a recreational area like Big River State Park to the north in Mendocino. But, so far, there isn’t a willing seller. Our challenge is to find a win-win solution for the landowner and the community. One option still to be explored is a land swap.

We have involved our elected officials in our efforts — Senator Mike McGuire has already brokered a meeting with the landowners, Sonoma County Parks, and others. We hope these talks will continue and bear fruit. Assemblyman Jim Wood visited our area, and Richard and I took him and his aide, Ruth Valenzuela, on a tour of the Magical Forest. Showing our elected officials this special place gives them a better understanding of why we are so passionate about saving it.

It’s going to take creative thinking, and willing hearts and minds, to accomplish our goal. But if we prevail, if the acts of ordinary people save the river, it will be an important example of what a community of people can do to protect the ecosystem that nurtures us.

# # #

This article first appeared in Wild Hope magazine, volume 4. Wild Hope can be purchased at Four-Eyed Frog bookstore in Gualala or online at wildhope.org.

Note: Photographs displayed in this online re-print of the article, “We Speak for the River,” are from Friends of Gualala River’s archive, and are not the same as those published in Wild Hope. FoGR is grateful to the many photographers who have granted us permission to use their work on our website.

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it