Friends of Gualala River and Center for Biological Diversity filed an Endangered Species Act lawsuit in September, 2020, against the Gualala Redwood Timber Company, to protect threatened and endangered fish, birds and frogs from the proposed “Dogwood” logging project which targets 100-year-old redwood trees in the floodplain of the Gualala River.

The following are excerpts from our Motion for a Preliminary Injunction (filed May 20, 2021) to stop the logging while the issues are resolved in federal court, along with conclusions and findings from the declarations by subject matter experts supporting the Motion. For readability, footnotes and references are omitted, but the entire documents are available in pdf format for those interested in the full technical details.

Motion for a Preliminary Injunction

Read the complete document:

2021 Dogwood ESA case: Motion for a Preliminary Injunction

plus supporting exhibits:

Declaration of Dominick DellaSala (owls)

Declaration of Christopher Frissell (fish)

Declaration of Sarah Kupferberg (frogs)

Declaration of Charles Ivor (FoGR)

Declaration of Jeff Miller (CBD)

Declaration of Stuart Gross (background)

[excerpt]

Introduction

The forest of the Gualala River floodplain, located on the border between Sonoma and Mendocino County, is among the southern-most redoubts of four of Northern California’s most iconic threatened and endangered species. Last logged over 100 years ago, broad, flat, and wellwatered by the Gualala River, the forest is primeval in quality, with towering redwoods and Douglas firs that evoke the old growth forests that formerly blanketed the coastal range to Santa Cruz and beyond. As those old growth forests disappeared, so did fish, birds, and amphibians that lived in them. Absent the preliminary injunction sought herein, this summer, GRT will log that forest, likely killing, harassing, and/or harming individual members of each of the Listed Species and causing irreparable harm to efforts to keep these animals from sliding into extinction.

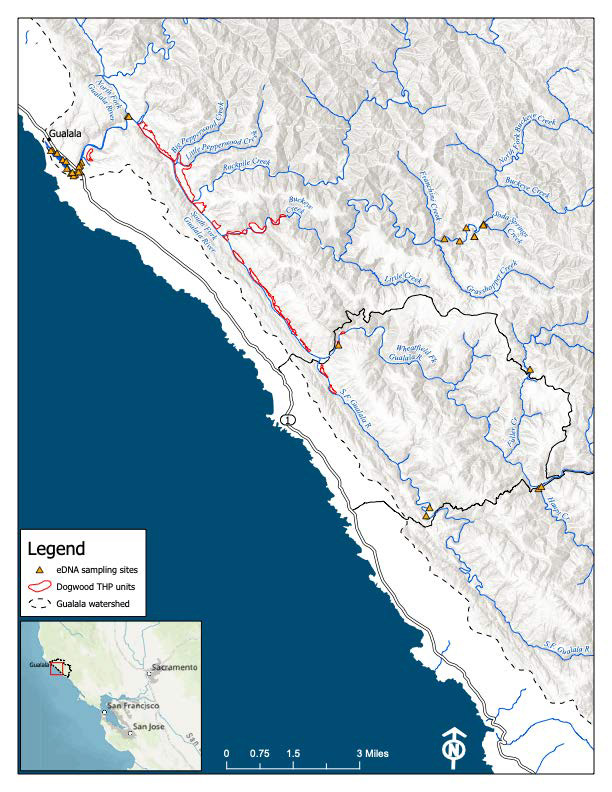

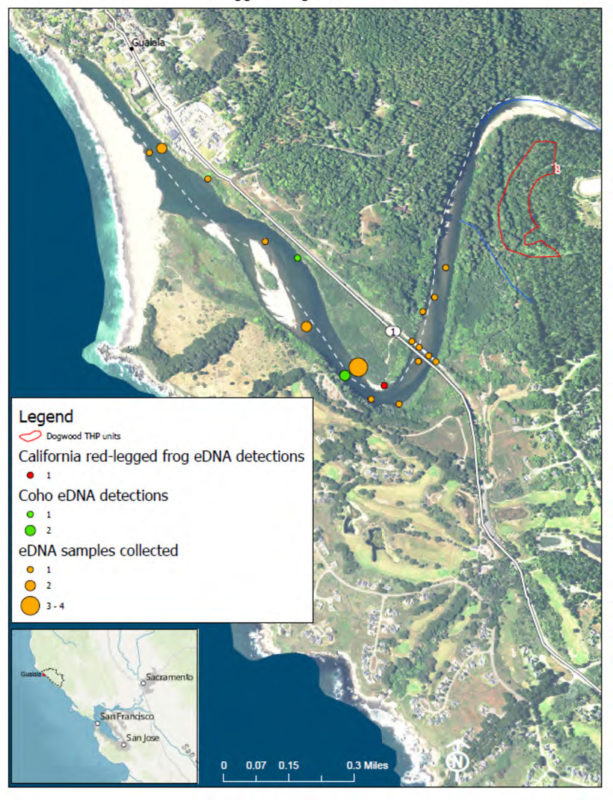

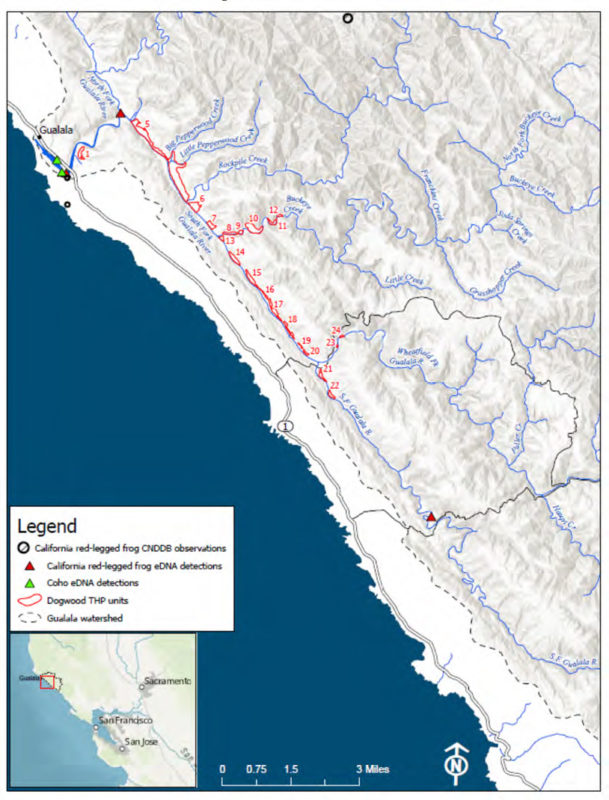

Plaintiffs are likely to prevail in their claims that the proposed logging is reasonably certain to result in the “take” of each of the Listed Species in violation of Section 9 of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”). There can be no dispute that each of the Listed Species occupies the forest to be logged. The occupancy of each is well documented, including, in the case of CCC coho, NC steelhead, and CA red-legged frogs, through environmental DNA (“eDNA”) sampling conducted by Plaintiffs last year. And the declarations by Plaintiffs’ experts – Drs. Chris Frissell, Sarah Kupferberg, and Dominick DellaSalla – outline multiple mechanisms by which the proposed logging is reasonably certain to kill, harm, harass, and/or harm the Listed Species. These include both direct take and indirect take through significant habitat modification and/or degradation that significantly impairs essential behavioral patterns of the Listed Species, including breeding, feeding, and/or sheltering. They further detail how these harms would result in species-wide impacts and delayed implementation of the Listed Species’ respective Recovery Plans, causing the type of irreparable harm that requires maintenance of the status quo while Plaintiffs’ claims are pending.

It is expected that GRT will, nonetheless, argue that it simply not possible for take to result because it intends to comply with California’s state law regulatory regime for logging and various associated take-avoidance guidelines regarding northern spotted owl, NC steelhead, and CCC coho. Indeed, GRT has intimated that it intends to argue this as a matter of law. The fallacy of this argument is multi-faceted. The only mechanism by which a party can, as a matter of law, avoid an ESA § 9 take finding, is by utilizing ESA § 10, to whit: creating a Habitat Conservation Plan (“HCP”) and obtaining an Incidental Take Permit (“ITP”) from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFW”) or the National Marine Fisheries Service (“NMFS”), as applicable. GRT has never done so with regards to any of the Listed Species. Moreover, USFW and NMFS have, in fact, repeatedly confirmed the inefficacy of the state law regulatory regimes on which GRT intends to rely, and have likewise confirmed that California’s take avoidance requirements are nowhere near as stringent as those required by an HCP. It is, therefore, not surprising that, as explained in the accompanying expert declarations, notwithstanding GRT’s promises that it will comply with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (“CalFire”), USFW, and NMFS’ guidelines for take avoidance, it is reasonably certain that take will not be avoided; and, in certain circumstances, it is not even possible for GRT to comply with the take avoidance measures, given baseline conditions.

These facts, which together show a likelihood of success on the merits and irreparable harm, together with those going to a balancing of the equities and public interest, entitle Plaintiffs to a preliminary injunction, and they respectfully request that the Court enter one, here.

FACTS

I. The Gualala River Watershed

The Gualala River flows through southern Mendocino and northern Sonoma counties about 100 miles north of San Francisco. The 298 square mile watershed consists of rugged mountainous terrain with erodible soils forested by redwood, Douglas fir, madrone, and tan oak. It is one of the few and evershrinking examples of mature redwood forests that once carpeted the Northern California coast. This lush riparian forest is the home of many different species of plants and animals, including the Listed Species; and each of the Listed Species depend on the riparian habitat in the watershed and the floodplain of the river. CCC coho and NC steelhead shelter, feed, and breed in the river and its tributaries, which, while essential to the survival of these species, are already damaged by sedimentation and nutrient loading from past logging, as well as temperature increases as a result of the reduced canopy coverage. The northern spotted owl uses that same dense canopy for nesting, roosting, hunting, and as a refuge from extensive predation by the invasive barred owl. And CA red legged frogs live and breed in the moist woody debris in the forest understory of the floodplain to be logged, as well as in the river itself and the surrounding off-channel pools and wetlands of the to-be-logged area. The Listed Species’ occupancy of this forest is despite the abuse that the Gualala River watershed has suffered over the last 150 years, which has, in turn, made the mature floodplain forests that GRT intends to log all the more essential for these animals. Intensive commercial logging of the watershed began in the 1860s and continued through the 1950s. The deleterious effects of that historical logging on the watershed and the flora and fauna that depend on it are well-documented and still keenly felt today. . . .

II. GRT’s Proposed Logging In The Dogwood Area

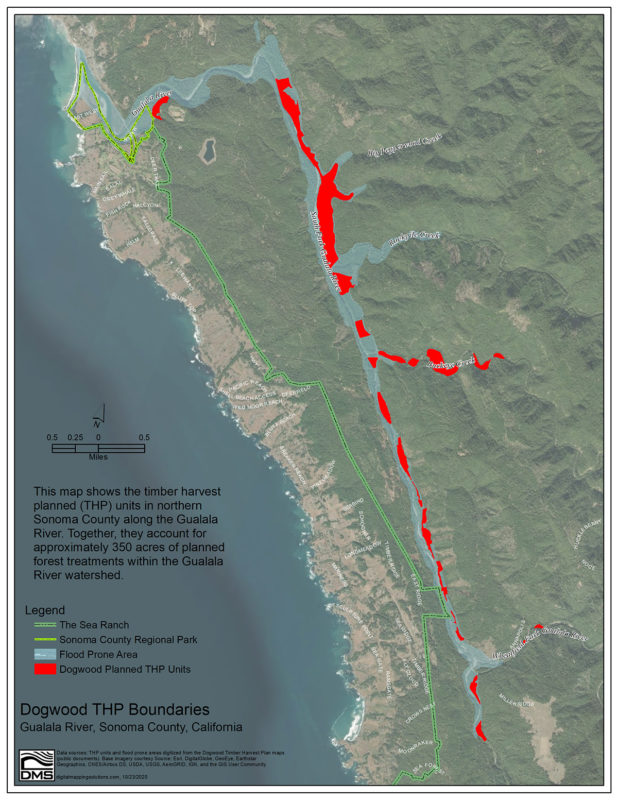

Pursuant to the Dogwood Timber Harvest Plan (“THP”), GRT plans to log redwood trees in the lower Gualala River floodplain, which was last logged approximately a century. The area to be logged is separated into 21 distinct units. The THP will primarily involve cutting mature second-growth redwoods ranging from 90 to 100 years old. Accomplishing this logging will require the use of heavy equipment within the floodplain, including tractors, skidders, feller-bunchers, and trucks. GRT will fell the trees, then drag them through the forest undergrowth to the dirt roads using skid trails. Landings – clearings carved out for the sorting and loading of logs for shipping – will be created for stacking the felled trees prior to being transported along the logging roads. The logging roads will be maintained by spraying them with water drafted from holes dug in the gravel bars of the Gualala River. In sum, GRT’s timber harvest will be accomplished by the use of invasive heavy equipment that will damage the forest canopy, undergrowth, the river itself, and the species that inhabit each.

III. The Endangered and Threatened Species in the Gualala River Floodplain

The Gualala River and its surrounding environs are home to the NC steelhead, CCC coho, northern spotted owl, and CA red legged frog. Each of these species is listed as “threatened” or “endangered” under the ESA, and all of them have been pushed to the brink of extinction, in large part as a result of commercial timber harvesting. GRT’s logging in the Dogwood area is reasonably certain to result in the take of each of these species and cause irreparable harm to each and the habitat that it depends on for survival.

A. The Northern California Steelhead

The NC steelhead is the anadromous form of the coastal rainbow trout, meaning that it migrates between fresh and salt water as part of its life cycle. Like all anadromous salmonids, including CCC coho, NC steelhead, with minor exceptions, always return to the rivers or streams they were born in. NC steelhead were listed as a threatened species under the ESA in 2000. In 2016, NMFS promulgated a recovery plan for the NC steelhead, citing the “inadequacy of regulatory mechanisms, destruction and modification of habitat, and natural and man-made factors” as the “primary causes for the decline” of the NC steelhead.

NC steelhead inhabit the Gualala River throughout the course of their life cycle — NC steelhead begin their lives as eggs in stream gravels, feed on tiny invertebrates in the water column as fry, spend 1-3 years in the stream until they are large enough to migrate through the estuary and into the ocean, then return to the stream to begin the process anew. Environmental DNA testing confirms the presence of NC steelhead throughout the lower watershed in which GRT intends to log, and although past and recent accounts of NC steelhead suggest the population is currently self-sustaining, the numbers of returning adult steelhead are highly variable and possibly declining. NMFS rates the following indicators for salmonid viability and watershed conditions in the Gualala River as “poor”: pool shelter, primary pools, pool/riffle/run ratio, impaired hydrology (passage flow for smolts), stream side road density, water temperature, and summer juvenile steelhead reduced density and abundance. The recovery plan identifies its focus for the river as: “improving these poor conditions as well as those needed to ensure population viability and functioning watershed processes.”

NMFS specifically identifies logging, wood harvesting, and roads associated with logging as “high threats” to the Gualala River NC steelhead population. Timber harvests result in the take of NC steelhead via impacts including reduced in-stream large woody debris, increased water temperature, and increased erosion and sedimentation. The recovery plan observes that “although logging has improved compared to historical practices, habitat degradation from past logging and potential impacts associated with future logging will continue to threaten the recovery of steelhead and their habitat” in the Gualala River. NMFS’ Gualala River Conservation Action Planning Viability Table ranks logging as posing the highest risk to NC Steelhead. And, at various points in the Recovery Plan, with regard to California’s regulatory mechanisms for avoiding take of Northern California steelhead, NMFS states that the applicable Forest Practices Rules “do not fully address the limiting factors for steelhead.”

B. The CCC Coho Salmon

The CCC coho is a species of anadromous fish, which, like the NC steelhead, migrates between salt and fresh water as part of its life cycle. Recent environmental DNA sampling (“eDNA”) confirms that CCC coho still maintain a presence in the Gualala River. CCC coho use the Gualala River during their life cycle in a similar manner to all anadromous salmonids — starting as eggs amongst clean stream gravels, sheltering and feeding amongst cover in the stream as juveniles, then migrating into the estuary and ocean as adults, before returning to breed. GRT’s impending logging project is likely to further harm this distressed population, which is on the brink of complete collapse.

NMFS released its Final CCC Coho Recovery Plan, in 2014, with the goal of restoring CCC coho to healthy, self-sustaining numbers. The recovery plan states that “[l]ogging and wood harvesting, severe weather, roads, and water diversion and impoundment” are the greatest threats to coho in the Gualala River. Like NC steelhead, timber harvests result in the take CCC coho via impacts including reduced in-stream large woody debris, increased water temperature, and increased erosion and sedimentation. These impacts have been shown to impair the reproductive success of CCC coho due to increased turbidity, loss of interstitial spaces for use by juveniles, the smothering of eggs by fine sediments, loss of deep pools, and blockage of spawning habitat by landslides.

With regard to the California’s Z’berg-Nejedly Forest Practice Act of 1973 and its regulatory regime for protecting salmonids, referred to as the “Anadromous Salmonid Protection” or “ASP” rules, NMFS’ CCC coho recovery plan specifically states that they do not adequately protect CCC coho. . . .

It is GRT’s claimed obedience to these ASP rules that it asserts will prevent take of CCC coho and NC steelhead, as a matter of law. They won’t.

C. The Northern Spotted Owl

The northern spotted owl is a medium-sized dark brown owl native to the Pacific Northwest. It requires older, multi-layered, structurally complex forests for habitat, and its population has been decimated by commercial logging over the course of the last century. USFW listed the northern spotted owl as “threatened” under the ESA, in 1990, citing in large part the loss and adverse modification of suitable habitat as the result of timber harvesting, and promulgated a revised recovery plan in 2011. The decline of the northern spotted owl has been specifically and repeatedly linked to habitat degradation caused by logging. Large trees, high canopy closure, and multiple layers of trees allow the owl to nest and perch in the shade during the heat of a summer day. The structural complexity of older forests also provides suitable habitat for canopy-dwelling prey species while offering large trees for hunting and nesting by northern spotted owls. Northern spotted owls are known to decline or abandon nesting territories when logging destroys or degrades structurally complex and older forest habitat. In addition to the actual destruction of northern spotted owl habitat, the removal of large diameter trees and related canopy reduction invites invasion and competition by the barred owl; a larger, more aggressive invasive competitor of the northern spotted owl.

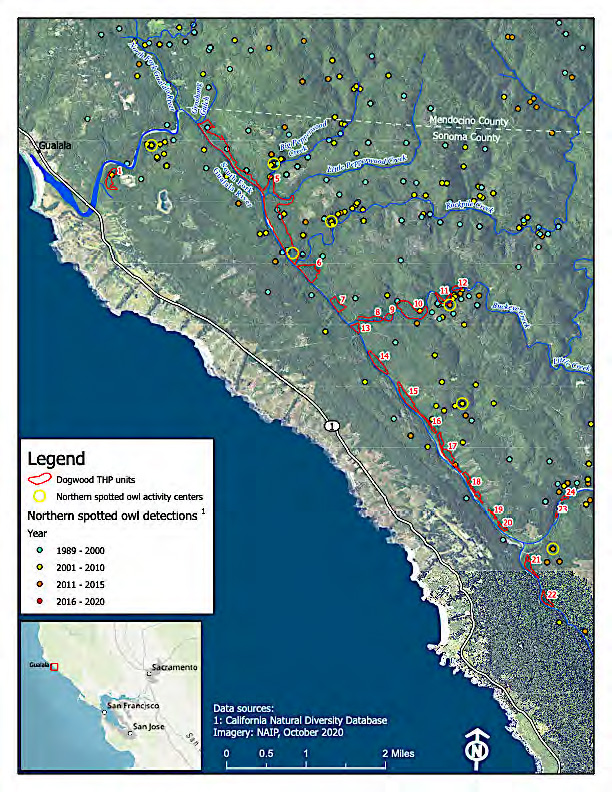

Northern spotted owls live in the Gualala River watershed. The large and mature secondary growth redwood trees in the riverine corridor in which GRT intends to log represents some of the last, best northern spotted owl habitat in the Gualala River watershed. GRT’s northern spotted owl surveys – mandated by state law – identify numerous northern spotted owl activity centers within or adjacent to the Dogwood THP, and its surveyors have made contacts with northern spotted owls in the area over the last several years, including as recently as March of 2020, though, for reasons discussed herein, these surveys are likely undercounting northern spotted owls. GRT’s logging are reasonably certain to cause take of the NSO by reducing the contiguous canopy they require for nesting, roosting, and feeding; as well as by increasing the likelihood of predation by the invasive barred owl.

D. The California Red-Legged Frog

The CA red legged frog is the largest frog native to the western United States. It has been extirpated from over 70% of its historic range and has suffered a population decline of 90%. USFWS listed the frog as a “threatened” species under the ESA in 1996, and promulgated a recovery plan for the CA red legged frog in 2002, which states “[t]imber operations and related practices occurring on commercial, private, and public timberlands within watersheds inhabited by the California red legged frog may contribute to the degradation of instream and riparian habitat and the decline of California red-legged frog and other aquatic species.”

The CA red legged frog requires both terrestrial and aquatic habitats for living and breeding. On land, it occupies moist woods, forest clearings, stream border vegetation, shrub, and grassland communities, and shelters in moist debris piles, mammal burrows, leaf litter, and under shrubs. It moves into aquatic habitats to breed, mating and reproducing in springs, marshes, ponds, and lakes, and in streams and rivers where there are microhabitats with slow moving water. The Gualala River and its surrounding floodplain are replete with suitable CA red legged frog breeding habitat, and CA red legged frogs are known to live the Gualala River floodplain and their occupancy has been confirmed by eDNA sampling. GRT’s logging will cause take of CA red legged frogs by crushing frogs that occupy moist microhabitats on the forest flood, destroying those same microhabitats, and reducing and interfering with their available aquatic habitat.

Declaration of Dominick DellaSala

Ph. D in Natural Resources from the University of Michigan (1986).

Read the complete document:

Declaration of Dominick DellaSala (owls)

[excerpt]

CONCLUSIONS AND FINDINGS

Based on my site visit, inspection of THP and satellite imagery, and knowledge of NSO habitat, logging treatments proposed in the GRT THP are unsupported by the literature on NSO habitat requirements and thus will cause irreparable harm of NSO at the local and species level. Specifically, minimal no-cut buffers and seasonal restrictions are clearly inadequate to avoid take and would likely lead to further collapse of the NSO population as the Gualala River corridor becomes increasingly permeable (canopy reductions) to Barred Owls and potentially Great Horned Owl depredation of NSO.

At least five of the logging units, already are operating below optimal nesting NSO habitat requirements despite statements to the contrary made by GRT during my site visit. I therefore conclude with reasonably certainty that implementation of the Dogwood THP will cause irreparable harm to individual NSO, NSO pairs, and young NSO seeking to reoccupy sites that are otherwise now reaching mature structural conditions and optimal nesting habitat. By enabling Barred Owl encroachment in the river corridor, logging also would likely harm NSO behavior (prevent territory defense via calling), survival of adults and young, and reproduction rates by intensifying competition with Barred Owls and possibly predation by Great Horned Owls.

– level of logging east and west of the river corridor (marked in red).

DellaSala).

Declaration of Christopher Frissell

Ph.D. in Fisheries Science, Oregon State University, 1992

Read the complete document:

Declaration of Christopher Frissell (fish)

[excerpt]

CONCLUSION AND FINDINGS

The cumulative outcome of all of the effects covered above is in my opinion an extremely high probability of take of steelhead and coho salmon by adverse habitat alteration,which not only damages habitat, but more seriously curtails or reverses the natural processes ofhabitat recovery that are currently underway on the Gualala River floodplain and nearby slopes.

Even if the individual sources of harm were each small in probability of occurrence (they are not), the sum of probabilities aggregated across the timber sale produces a large probability of take. The chain of cause and effect of habitat modification extends from the floodplains of the South Fork Gualala and its tributaries downstream to the Gualala estuary. Importantly, none of the actions proposed in this timber sale has a foreseeable positive effect or benefit to habitat of protected steelhead and coho; at best they are effective in partially limiting the harms that will be done.

The sources of take of steelhead and coho salmon I identified can be summarized as follows:

1. Logging Removal of large trees Curtails Recruitment of Wood and Depletes Natural Wood Loading in Aquatic and Floodplain Habitats.

The depletion of wood recruitment to floodplain s and channels by selective logging is not offset by growth release of uncut trees, because thinning directly nullifies a portion of the natural self-thinning processes that produce dead and downed wood. Moreover, thinning is controversial in the forestry community. Thinning is a means of harvesting wood, but it is not a necessary means to “restore” floodplain redwood forests, which recent research establishes are perfectly capable of restoring themselves in the absence of thinning.

2. Tractor logging and yarding directly damages floodplain channels and wetlands that are the key wintering habitats of steelhead and coho salmon.

Because these essential habitats are both widespread within South Fork Gualala floodplains and sensitive to direct disturbance, any extensive ground-based logging operations across these floodplains are highly likely to adversely modify them. Skid trail locations flagged on steeper slopes in Dogwood Unit 1 are already sites of ongoing erosion from past logging on the site.

3. Haul roads are configured such that they deliver chronic fine mineral sediment to river, tributary, and floodplain habitats.

Delivery of this road-generated fine sediment to waterways is an intrinsic, systemic problem wherever roads are superimposed on a floodplain and closely parallel and cross numerous aquatic and wetlands habitats. Roads in the sale area show relatively little evidence of the kind of design features and maintenance that are necessary to effectively direct sediment laden road runoff away from surface waters and wetlands.

4. Logging on floodplains will produce summer stream temperature increases in streams where temperature already limits salmonid survival and productivity.

Canopy reduction of the magnitude anticipated in Dogwood units causes shade loss sufficient to measureably warm streams that are today already warmer than growth and survival optima for steelhead and coho salmon.

5. Logging that increases erosion and delivery of sediment also delivers nutrients to a highly nutrient loaded river, increasing harm from algae blooms and eutrophication in the river and estuary.

This threat to juvenile steelhead and coho salmon rearing in the river and estuary, though not sufficiently informed by existing analyses and data, is also not mitigated by proposed or current practices, and likely poses the greatest single threat of mass mortality and potential extirpation of their populations in the Gualala.

off the main South Fork Gualala Road haul route for Dogwood timber sale in Unit #5.

Just beyond the patch of deep shade between the two redwoods, this skid trail fords the

floodplain springbrook seen in photos 7 and 8. There is no culvert or other crossing

structure; heavy equipment travels through rather than around or over the springbrook. In

such circumstances, skid trial use collapses streambanks, disturbs the streambed and

destabilizes any wood debris present in the stream at the crossing site, and mobilizes

clouds of fine sediment that cause turbidity plumes in the springbrook habitat

downstream. I observed flag markers designating unbridged ford crossings of floodplain

channels and swales in multiple units of the Dogwood timber sale.

Declaration of Sarah Kupferberg

PhD Candidate, U. of Washington, School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences

Read the complete document:

Declaration of Sarah Kupferberg (frogs)

[excerpt]

CONCLUSION AND FINDINGS

I find that the mitigation measures in the THP are insufficient to protect Red-legged Frogs from harm because there is a mismatch between the extensive area of the proposed activities and the limited designation of suitable habitat and buffer zones. The narrow buffer zones around aquatic habitats are incongruous with the numerous places where frogs could occur on land and underground, so I conclude that harm to Red-legged Frogs will likely be unavoidable.

It is reasonable to expect that the physical disturbances created by falling trees, yarding, skidding, building roads, installing river crossings, using heavy machines, and drafting, will overlap with the places Red-legged Frogs occur. Where and when the proposed activities and Red-legged Frogs coincide, harm, harassment, or mortality of individuals, destruction of habitat, and diminution of the frogs’ food resources are likely.

Because Red-legged Frogs are vagile, difficult to detect on land and in underground shelters, effective avoidance and mitigation relies on establishing sufficiently large non-logging zones around aquatic habitats to prevent harm. My professional opinion is that to avoid take of Red-legged Frogs, GRT should implement the maximum buffer zone of 1 mile around aquatic habitats as recommended by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service in their recovery plan for this species.

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it