Location

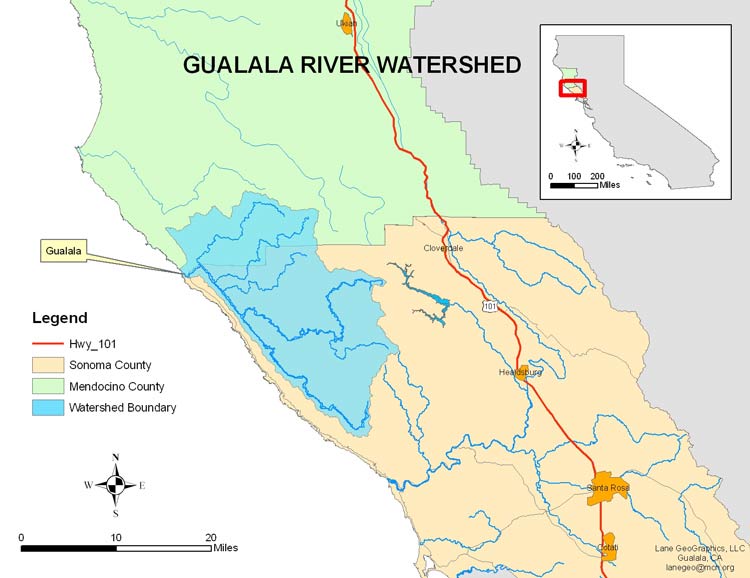

The Gualala River enters the Pacific Ocean approximately 110 miles north of San Francisco, California. Just past the mouth of the river lies the town of Gualala, a three-hour drive from San Francisco over narrow, twisting roads and stunning ocean and mountain views. Tourism and logging are the primary local industries.

Land area

The Gualala River watershed covers 298 square miles, and spans the Sonoma / Mendocino County line. About three-quarters of the watershed is in Sonoma County, and constitutes 14% of that county. The other 25% of the watershed makes up 2% of the much larger Mendocino County.

Population

2000 Census results show 6,971 residents in the area between Jenner and Manchester (a range of approximately 50 miles, with the Gualala River just past its halfway point).

Census information also shows that 40% of the houses are vacant (mostly vacation houses and rentals), suggesting a weekend population of approximately 11,618 full and part-time residents. These numbers do not include hotel / motel / B&Bs guests.

About the River

The water flow is extremely variable from summer to winter months. Local annual rainfall averages are approximately 36 inches along the coast and 72 inches inland. A large sandbar usually blocks the mouth of the river from late spring until the heavy rain runoffs of late fall.

The river’s source lies in the high coastal range watershed, and its main forks rest directly on the San Andreas fault line. The river is approximately 32 miles long and works its way through 190,000 acres of rugged countryside.

The river is a breeding ground for the threatened coho salmon and steelhead trout as well as other local fish. Ospreys, great blue herons, egrets and river otters fish in the river and its estuary.

Although the river was once internationally known for fishing, 100 years of logging has so damaged the habitat that the coho are now nearly extinct. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) includes the Gualala River on its Clean Water Act 303(d) list for excessive sediment and high temperatures. The EPA has published a report on Gualala River Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for Sediment. Local volunteers and state and federal agencies are working to restore the river, but its health remains fragile.

There are currently three main threats to the river. Large scale logging operations contribute to sediment in the river and raise water temperature.

Growing pressure for vineyard conversions would likely result in increased pollution from pesticides, and would have the same damaging effects as clear-cut logging, but would also clear all vegetation and would not replant trees.

A recently defeated commercial plan to remove water from the river approximately one mile above the mouth would have further degraded the river, and could have been the last straw for this unique and beautiful river.

For those seeking further details on the watershed, the North Coast Watershed Assessment Program (NCWAP) has released a detailed report on the Gualala River watershed. NCWAP is a state funded effort working with local landowners, and defines its activities as gathering data “to improve watershed and fisheries conditions” on California’s north coast. [See: excerpt on vineyard conversions.]

The Institute for Fisheries Resources has also published a database of detailed information on the Gualala River watershed (called KRIS-Gualala), which includes extensive text, tables, maps and photographs.

Water Quality

Information on water quality for municipal water systems which draw from the Gualala River underflow is available from the Environmental Working Group:

Water Quantity

Information on the quantity of water flowing in the Gualala River is available from the United States Geological Survey:

Gualala River water flow data

Local History

The original occupants of the Gualala Watershed were the Kashia Pomo Indians. They referred to the area as qhawálaoli, “water coming down place” or “where the sky (also river) meets the sea.” With the arrival of the first Russian settlers, timber harvesting became the area’s first industry.

Virgin old growth redwood was removed as early as 1862. As timber demands grew after the 1906 earthquake, more and more old growth was harvested. Logging activities slowed somewhat in the 1960s, but still continue today.

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it