genus Sequoia, family Cupressaceae (cypress)

An Unparalleled Species

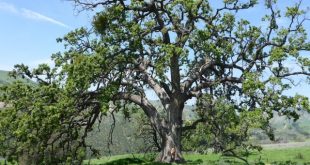

The most iconic tree species in our region is the Coast Redwood. [Photo 1.] Its presence in the Gualala River watershed is deeply historic, it is a species central to the ecology and economy here, and it is perhaps the most remarkable tree species on earth.

Redwoods are the tallest beings on the planet with specimens growing well over 300 feet in height, so famous that the tallest trees in our northern forests bear individual names like Atlas, Icarus, Zeus, Stratosphere Giant. Because of their colossal size, redwood trees are hugely productive, supporting, on average, many more tons per acre of biomass than even tropical rain forests.

Redwoods are also among the oldest trees–some individuals live more than 2000 years–and they are an ancient lineage. During warmer wetter periods as many as 140 million years ago, redwoods covered much of the western continent. At one time Sequoia was believed to have been the most widely distributed conifer, extending from the north pole down to the mid-latitudes. But as the climate cooled and dried, its range shrank to a narrow forested band running some 450 miles along the Pacific coast from southwestern Oregon in the north to southern Monterey County.

Scientists who study redwoods have divided the range into 3 subregions– northern, central, and southern–because their different soils, climate, and other factors have created varying conditions for adaptation. The Gualala River watershed lies within the central region which extends from southern Humboldt County to northern San Francisco Bay. [Photo 2a.]

The redwood forest is a great reservoir of water, with each tree “exhaling” through transpiration up to 500 gallons of water a day. Within the fog-enshrouded belt of the Northern California seacoast, the trees reach their greatest size and density, hence our regional nickname, the Redwood Coast. In big tree stands, the massive trees create their own internal weather of relatively constant moisture and moderated temperature. The forest canopy captures fog which condenses and drips to the forest floor, supporting a unique lush understory of ferns, mosses, wildflowers, and shrubs. [Photo 2b]

Light conditions in the redwood forest range from deep gloom to dappled shade, created when lower branches of the trees drop off allowing light to penetrate. [Photos 2c. 2d. 2e.]

Among the ecological wonders of the old-growth redwood forest is the occurrence of canopy ecosystems which were first discovered in redwoods in the 1990s when Dr. Steven Sillett, his wife, Dr. Marie Antoine, and their colleagues climbed to the tops of these titans. There among the vegetation growing in the crowns were animals such as salamanders, insects, and mollusks that spend their lives in the treetops. Thick mats of soil from needles and other debris accumulate in the tree tops and provide a rich environment for these animals as well as for a variety of ferns, mosses, shrubs and even other trees. While previous research into tree canopies focused on the much shorter trees in tropical forests, the twin discoveries of canopy life in the titan redwoods of temperate rain forests and the techniques for climbing them spawned a whole new area of scientific exploration around the world.

Natural History of the Redwood

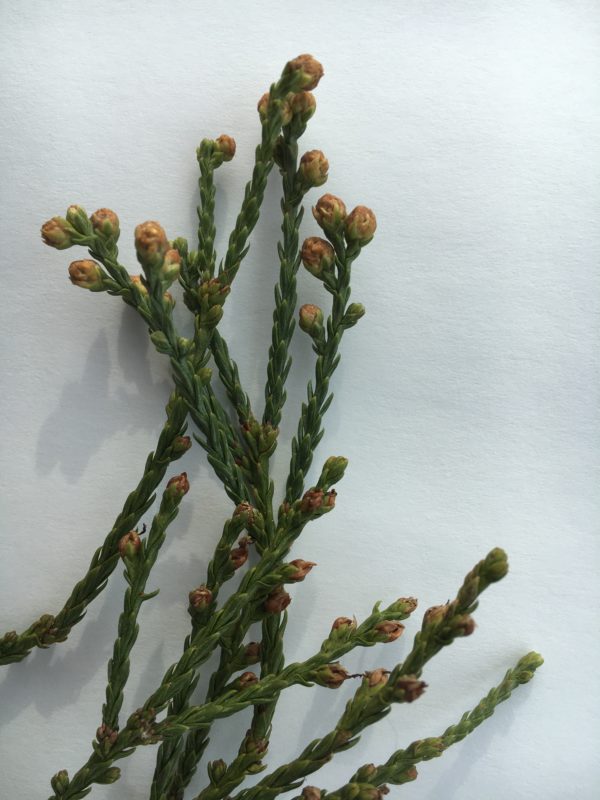

In late January the life cycle of the redwood begins when tiny male cones appear on the tips of branches releasing pollen into the air that will fertilize the larger female cones. [Photo 3.]

In late fall the female cones release mature seeds about the size of tomato seeds that are dispersed by the wind. [Photo 4.] Most seeds do not germinate, but some that fall on hospitable sites such as exposed silt or fallen logs may sprout.

The needles of the redwood occur in two types: the top-most branches that are more exposed to the sun are scale-like, while lower branches have flat needles that remain on the branchlets even after they have fallen from the tree. [Photos 5,6,7.] The tree roots are shallow and spread through the soil across great distances in a network that supports their enormous size.

One key to the longevity of the species is its capacity to stump-sprout. Much of the second growth redwood forest is composed of rings of clones growing out of old-growth stumps. [Photos 8. 9.]

These daughter trees possess the same genes as the original tree and are capable of extending the lineage of the tree indefinitely. The tree also forms large burls, masses of tissue composed of dormant buds that can sprout. [Photo 10.]

Other key adaptations include thick fibrous bark that resists fire and natural chemical compounds that resist rot and damage by insects. [Photo 11.] One rare trait of redwoods–unique among conifers– is that they possess 6 sets of chromosomes, a characteristic which may confer more genetic plasticity to the species.

While individual trees can live a long life, when they do die and topple to the forest floor, their role as decomposing downed logs in the ecology of the forest floor is critically important. There they support many species of moss, lichens, and fungi which in turn provide habitat and nutrients for a large array of animals and other plants. [Photo 12.]

The Economic Importance of Redwoods

Perhaps no other tree in California has proved so useful and economically valuable than the coast redwood. It continues to be at the heart of bitter disputes between those who view the tree as primarily an economic resource and those who value its ecological significance and wish to protect it.

It is easy to see why the timber industry regards the redwood as a valuable product. The wood has remarkable qualities. Its beautiful straight grain makes it easy to work with and desirable for building. Burl wood is a dark heavy wood prized by wood workers for its elaborate figures. From a forester’s perspective, big redwood trees are valuable because of the relatively larger amount of heart wood which is of the finest quality, resistant to rot and insect damage.

Before logging began, some 2,000,000 acres of old-growth redwood existed, and then the forests were logged as if there were a limitless supply. Today we speak reverently of these virgin trees that are centuries old because there are so few of them. Fewer than 100,000 acres of old-growth redwoods survive, and even with efforts to conserve them, some scientists believe that the environmental conditions that produced these magnificent forests no longer exist, particularly given the effects of climate change.

The Gualala River watershed has its own history of redwood logging. Within the short span of 100 years, extensive logging of the old-growth trees decimated the stands, with those in the Gualala River watershed among the first to go because of their proximity to the burgeoning city of San Francisco. It is said that old-growth Gualala redwoods built San Francisco twice– first before and then after the fire that accompanied the 1906 earthquake that destroyed so many homes. Their massive stumps are visible everywhere within the western portion of the Gualala River watershed, a sad testament to a bygone era.

In the Gualala River watershed, almost all of the redwood forest is second growth or younger, the largest and oldest trees having been logged off [see also: California’s towering redwoods face uncertain future, report says]. Logging is one factor that has changed the composition of the forest toward more of a mixed conifer forest with the increasing occurrence of Douglas fir, since its seeds germinate more readily and in greater numbers in the openings left by logging than do the redwoods. Loss of old-growth redwoods has changed much of the natural environment of the watershed including its soils, hydrology, vegetative cover, and wildlife.

Associates of the Redwood Forest

While redwood forests in the 3 subregions share many of the same species of plants and animals, there are differences too, some based on biotic factors, others on the degree to which the forests have been logged or converted to other uses. There is no such thing as a generic redwood forest. No comprehensive survey has been made of plants and animals associated with the redwood forests of the Gualala River watershed, and since most of the land is private, access is restricted. Some limited surveys have been done for timber harvest plans, but these are not comprehensive. Nonetheless, many species have been observed and photographed. It’s impossible in this brief description of redwood trees and forests to document every species. Instead we touch briefly upon some of the known associates of our redwood forests. A more comprehensive list of watershed species is being developed by FoGR.

Animals

Despite the loss of old-growth redwoods in the watershed, the remaining forests still support many species including the Northern Spotted owl, a threatened species most closely associated with old-growth redwoods. Many species that have been observed and photographed range from the black bear and mountain lion down to the smallest invertebrates. Here are 3 humble species commonly encountered that make their home primarily along creeks and on the moist forest floor: Oregon salamander, the banana slug and the California giant salamander. [Photos 13. 14. 15a. 15b.]

There are also numerous aquatic species associated with the river itself as it flows through the redwood forests. California north coast rivers, including the Gualala, once supported enormous runs of 4 species of salmon and the Steelhead Trout, and the Gualala River was known for its fantastic fishing. But in recent decades impacts from logging–especially sediment from logging roads and the loss of canopy shading the river–together with warming ocean waters have decimated the salmon runs. Today, while the steelhead can still be found throughout the main forks of the Gualala River, only the north fork supports Coho Salmon.

In addition to salmonid fish, many other aquatic species are associated with the Gualala River.

Plants

While redwood forests are not known for the highest diversity in plant species, they are home to some of the most beautiful. Acid-loving plants, including the lovely flowering California azalea and rhododendron, thrive in the tannin-rich soils. [Photo 16.]

Perennials like redwood sorrel, star solomon seal, and redwood ivy create carpets that spread primarily through rooting. [Photos 17. 18. 19.]

Other perennials like Clinton’s bead lily, western trillium, star flower, and vanilla leaf appear seasonally, bloom, fruit and die-back. [Photos 20. 21. 22. 23.]

While few species of native grasses occur in redwood forest, the fragrant vanilla grass is a common associate as are different species of sedges. A diverse flora of ferns thrives: sword ferns dominate the understory, and creek banks support other species including lady, five-fingered, deer, and chain fern. [Photos 24. 25. 26.]

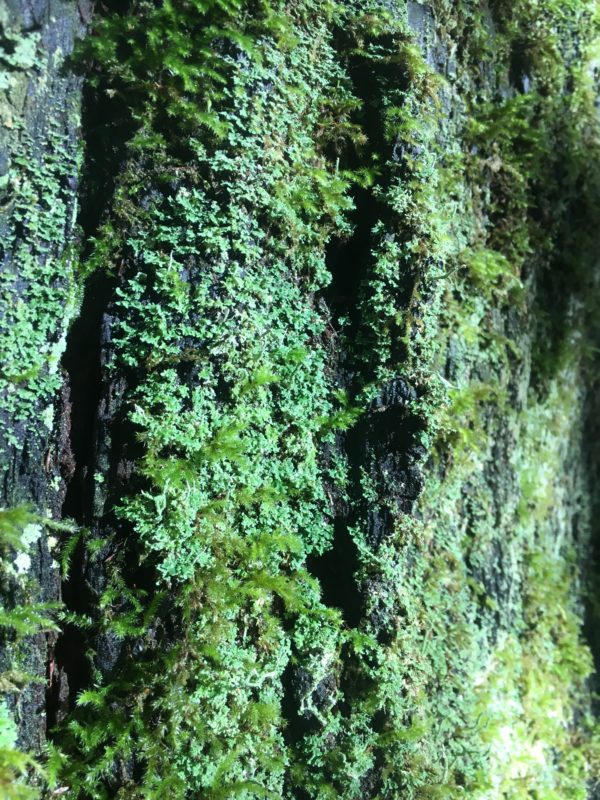

Mosses are nearly ubiquitous, and they help soak up and retain moisture. Together with algae, lichens and fungi, the mosses form thick living mats that drape over soil and logs which in turn become nutrient and water sources for other species. [Photos 27, 28.]

Fungi

Over 300 species of fungi are known to occur in redwood forests, forming an essential part of their ecology. Some live in the roots of the trees (endomycorrhizal associates) which help funnel water and nutrients to the trees in exchange for carbohydrates that the tree provides from photosynthesis. Some fungi are saprophytes and feed upon dead debris–whether needles or logs–breaking it down and making the constituents available for other organisms. For example, the often brilliantly colored waxy caps are saprophytic and are associated with mosses. [Photo 29.] And some fungi are pathogens that attack the redwood tree. These play an essential role in providing fallen logs which in turn are an important part of the ecology of the forest.

Lichens

Lichens are a symbiotic life form created by a species of alga in partnership with two species of fungi. They are a prominent feature and an important part of the ecology of the watershed. While our watershed is rich in species of lichens, only some of these occur in the redwood forest with other tree species, such as Douglas fir, supporting a richer lichen flora. One of the most visible lichens in the redwood forest is the Pacific Dust Lichen (Lepraria pacifica) which forms a light green powdery film that often coats the lower trunks of the trees. [Photo 30.] Others that are prevalent are various species of Cladonia, that inhabit soil, rock, or moss and that thrive in shady microhabitats where moisture accumulates.

Where to See Redwood Forests and Large Individual Trees

While redwoods are found throughout much of the watershed, the best examples of large trees and redwood forests available for the public to see can be found along the floodplain of the Gualala River in what locals call “The Magic Forest.” Enter the Gualala Point Regional Park’s campground and follow the trail that leads along the southeastern bank of the river. Other examples are found in the Soda Springs Reserve (east on Soda Springs Road off of Annapolis Road) as well as at the point of public access along Skaggs Springs Road where Haupt Creek joins the Wheatfield Fork at the Haupt Creek Bridge.

Selected Sources

Jackson, Jeanne A. 2014. Mendonoma Sightings Throughout the Year.

Kauffmann, Michael E. 2013. Conifers of the Pacific Slope.

Lanner, Ronald M. 1999. Conifers of California.

Noss, Reed F. 2000. The Redwood Forest: History, Ecology, and Conservation of the Coast Redwoods.

Preston, Richard. 2008. The Wild Trees.

All photos on this page courtesy of Laura Baker

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it