California Bay Laurel, Bay, Pepperwood, Oregon Myrtle, California Olive, Spice Tree, Headache Tree

(Umbellularia californica)

Family LAURACEAE

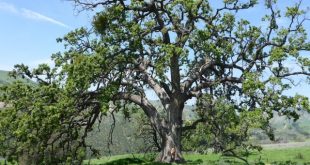

February is an excellent time to see flowering California Bay Laurel, though it can bloom as early as November and well on into spring. One of the more commonly occurring trees throughout the Gualala River watershed [Photo 1.], this evergreen hardwood species has many aliases but is probably best known for the spicy fragrance of its leaves–hence the common name, Pepperwood. While the bay leaves that are sold commercially as a spice come from a different but related tree, our own native tree leaves can be used for flavoring as well, but be careful–a little goes a long way!

Identification and Natural History

The bay is a distinctive tree in California–the only native species in the ancient family Lauraceae to occur in the state. Its range runs from the Umpqua River in Oregon along the Pacific coast ranges where it reaches its greatest size and into the western slope of the Sierra Nevada to northern Baja. It is a companion tree found in redwood, mixed conifer, and hardwood forests and occurs as a wind-pruned, low-growing shrub along the coast. [Photo 2.]

Bay leaves are shiny green and lance-shaped with a distinct crease running lengthwise. [Photo 3.] New foliage often takes on a bronze color. [Photo 4.]

The name of the genus–Umbellularia–is derived from the rounded groups or umbels of the flowers which are a creamy yellow and appear at the base of the leaves. [Photo 5.] The fruits are ovoid, like a small avocado which is a relative in the same family as the bay. [Photo 6.] They appear in the fall, drop from the trees and germinate soon after.

Unlike many broad-leaved trees that have a distinct outline, the bay is the shapeshifter of the arboreal world. It occurs in surprisingly different forms depending upon local conditions. It can grow to 100 feet in height in protected conditions but is subject to severe wind pruning near the coast. On the highest exposed ridges, such as along Tin Barn Road, can be found trees with large canopies, short stout trunks, and enormously wide bases that exceed 25 feet in diameter. [Photos 7, 8]

The bay trees that occur in the Gualala Point Regional Park camping area by the river exhibit a wide variety of growth forms. The bay is an eager and dense sprouter, and in the dense shade of the redwood forest some bays take on multi-trunked, spindly, upright shapes [Photos 9,10], which may be clonal clusters. In deepest shade, large branches lie down horizontally and continue to send up vertical offshoots. [Photo 11.]

Along the river banks, where there is abundant light, the trees develop massive knobby trunks that look like something out of a fairy tale forest. [Photo 12.] They begin as young trees bending toward the light. [Photo 13.] Their roots help stabilize the soil in the banks. Over time, the branches thicken and lengthen, and the erosive forces of the river begin to eat away at the soil. [Photo 14.]

Eventually the heavy branches pull the trees over where they may land on a gravel bar, but the river inexorably scours away the last of the soil from the roots,and the tree dies. [Photos 15,16.] Ultimately the river claims the trees when they sink to the bottom. There, as logs, they take on a new important role as large woody debris that provides vital habitat for salmon and steelhead. [Photo 17.]

Ecological Relationships

The ground beneath bay trees is often bare of other vegetation, perhaps because of a possible toxic effect of the aromatic oils in the leaves, though there is no direct proof of that yet. [Photo 18.] The oils may also help protect the leaves from insect damage, but have no inhibitory effect on deer which will browse saplings down to the ground. [Photo 19.]

Unlike the leaves of the bay, its flowers, which appear early in the year, may be of importance to insects seeking nectar or pollen. Small rodents, wild pigs, and bears consume the fallen fruits (Peter Baye pers. comm.), while sapsuckers–a type of woodpecker–probe the trunk for nutritious sap, leaving their telltale rows of holes in the bark. [Photos 20, 21]

Bay trees host a rich epiphytic community. Their thin, flat bark is often covered in ferns, mosses, and lichens [Photo 22, 23] Unlike many tree species, bays do not form ectomycorrhizal relationships with fungi, so it is unusual to find mushrooms growing under them, though Hygrocybes and Leptonias are reported to occur occasionally in the duff.

One species of fungus that is closely associated with bays is Ganoderma brownii, a saprophytic shelf fungus found frequently on dead bays. [Photos 24, 25]

This polypore fungus is known as the Western Artist’s Conk because the white pore surface darkens instantly when damaged. [ Photos 26, 27, 28]

Remarkably, individual specimens of this fungus are capable of living up to 50 years. They should not be collected. Turkey tail (Trametes versicolor) and pleurotoid mushrooms also feed on dead bay wood. [Photos 29, 30]

In recent years, the bay tree has taken on a new and unfortunate role as the most important vector of Sudden Oak Death, (Phytophthora ramorum), a pathogenic water mold that has decimated oaks in California. Though the pathogen does no significant damage to the bay other than leaving a tell-tale signature of black deadened area at the tip of the leaves, spores from infected leaves are washed with rain onto nearby oaks which are highly susceptible. [Photo 31.] SOD has been making its way across the watershed. Trees in moist shaded spots are hardest-hit.

Practical Uses

Native Americans and early settlers used bay leaves for a variety of medicinal purposes. The nuts were roasted and eaten. The wood of the bay tree (often referred to as myrtle wood) is famous for its lovely smooth grain and high polish which makes it unsurpassed as a finishing wood or for turning bowls, vases, etc. Old time loggers would drop newly cut bays into the nearest river where they would sink. Later they were retrieved and the wood which had darkened while in the water was called black myrtle wood.

Selected Sources

Baye, Peter. Local botanist and coast ecologist. Personal communication.

California Oak Mortality Task Force. www.suddenoakdeath.org.

Jepson, Willis Linn. 1910. The Silva of California.

Peattie, Donald Culross. 1948. A Natural History of North American Trees.

Siegel, Noah and Christian Schwarz. 2016. Mushrooms of the Redwood Coast: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fungi of Coastal Northern California.

Sudworth, George B. 1967. Forest Trees of the Pacific Slope.

All photos on this page courtesy of Laura Baker,

except #6 and #20, courtesy of Peter Baye.

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it

Friends of Gualala River Protecting the Gualala River watershed and the species living within it